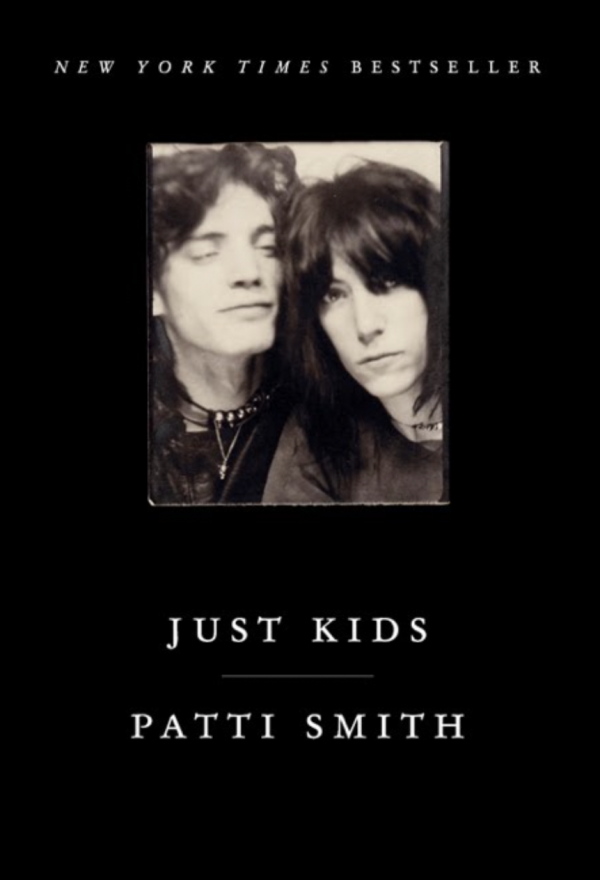

I started reading Just Kids yesterday afternoon, when Jimmy went to get his hair cut.

I kept reading through the Astros’ World Series game against the Atlanta Braves and what I thought would be a constant interruption—Halloween trick-or-treaters. But the doorbell only rang once the entire night, enabling me to stay immersed in the story of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe’s romance. My eyes were hurting and my vision was fuzzy when I finished it this morning.

I get why it won the National Book Award. I was and am still unfamiliar with most of Patti Smith’s body of work. Now I know she is, first and foremost, a poet. There is so much great writing in the book, my usual habit of highlighting good lines would’ve rendered whole pages yellow.

I knew almost nothing about Robert Mapplethorpe either, except that I had once looked at his work and found some of his photographs too disturbing to face. In the book, Patti mentions feeling the same way about some of his work. “I admired him for it, but I could not comprehend the brutality. It was hard for me to match it with the boy I had met.”

The boy she had met, in Tompkins Square Park in New York City when they were both around 20 years old, was kind and caring. He had been raised in a cold, non-communicative Catholic family. His dad wanted him to either enter the military or become a graphic designer. Robert knew he was an artist and rejected those paths.

Patti has a reverential attitude toward artists. During childhood, her family made exactly one visit to an art museum together (there were 4 kids and her parents didn’t have a lot of money). Afterward, she felt changed. She wanted to be an artist, but she had a private concern. She mentioned a movie, The Song of Bernadette. She was “struck that the young saint did not ask to be called. It was the mother superior who desired sanctity, even as Bernadette, a humble peasant girl, became the chosen one. This worried me. I wondered if I had really been called as an artist. I didn’t mind the misery of a vocation but I dreaded not being called.”

In their sweet, youthful relationship, Patti and Robert took care of each other. Even after they realized they were heading in different directions, they vowed to continue supporting each other until they both could stand on their own. They would draw, side by side, in their apartment, for hours at a time and into the night. Together, they shopped for dimestore trinkets and found “trash” that was elevated to treasure in Robert’s early collages.

An especially enjoyable aspect of the book is the building suspense regarding how and when he would finally begin taking photographs and she would begin writing songs and performing with a band.

Interestingly, while he was making extremely provocative and polarizing work, Robert was urging Patti not to make work that was too confrontational or controversial. He wanted her to make hits–“music he could dance to”–and be successful.

After they both had achieved some success, they had a joint gallery show of their work. For the show, they made a short film, in which Patti shared an idea that she and Robert had often discussed:

“The artist seeks contact with his intuitive sense of the gods, but in order to create his work, he cannot stay in this seductive and incorporeal realm. He must return to the material world in order to do his work. It’s the artist’s responsibility to balance mystical communication and the labor of creation.”

I was glad she mentioned this, because I’ve always wondered if it’s “natural” that one has to actually make the art. Shouldn’t it just appear, effortlessly? But that would require magic, right? So, I’ve always arrived at the same conclusion: apparently you do have to actually do the messy, real-world work of making the art. But reading the above quote was reassuring.

When I finished the book and closed it, I resented having to re-enter normal life. I wanted to stay in the world she created.

There are more passages I want to share, but I’ll choose just one. I hope it’s okay that I’m sharing it. It’s her description of having seen a swan when she was very young:

“The narrows of the river emptied into a wide lagoon and I saw upon its surface a singular miracle. A long curving neck rose from a dress of white plumage.

Swan, my mother said, sensing my excitement. It pattered the bright water, flapping its great wings, and lifted into the sky.

The word alone hardly attested to its magnificence nor conveyed the emotion it produced. The sight of it generated an urge I had no words for, a desire to speak of the swan, to say something of its whiteness, the explosive nature of its movement, and the slow beating of its wings.

The swan became one with the sky. I struggled to find the words to describe my own sense of it. Swan, I repeated, not entirely satisfied, and I felt a twinge, a curious yearning, imperceptible to passersby, my mother, the trees, or the clouds.”

Just Kids is, for me, like that swan was for her. It’s magnificent, and it evokes a curious yearning—the desire to be able to express myself the way she learned to do.